how can we control drug nanoparticle crystallinity?

understanding drug nanoparticle structure using molecular simulations

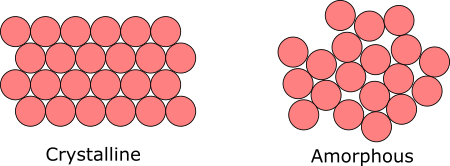

This paper was the second in my PhD, and was a really exciting foray into using molecular dynamics simulations to understand material systems. A previous PhD student had observed that when we make drug nanoparticles using the technology my group has developed, the ‘crystallinity’ (or percentage of the nanoparticle that is crystalline vs. amorphous, see the image below) was extremely difficult to control.

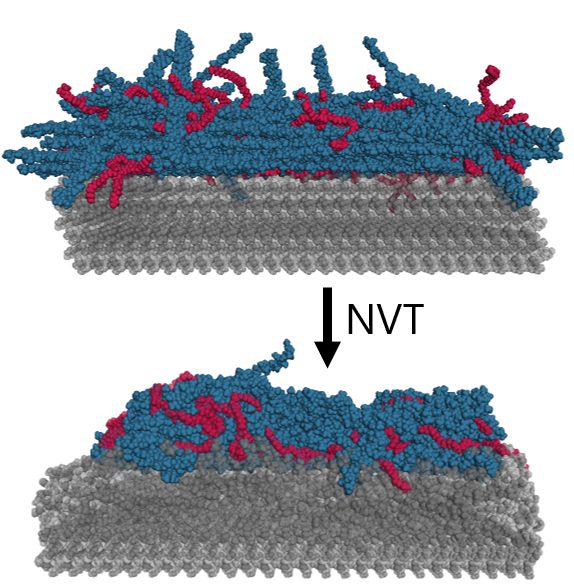

Crystallinity is crucial to drug formulation because it impacts how quickly a drug dissolves, which directly affects its bioavailability—the extent to which the active drug is absorbed and becomes available in the body. So, the lack of control we observed experimentally posed a challenge that we wanted to understand and ultimately mitigate. Since we were looking at molecular-scale interactions, I turned to molecular dynamics simulations (using GROMACS) to understand what interactions governed this behavior. We modeled our system by building a nanocrystal surface of our drug, then treating that surface with different ratios of excipients.

We looked at how the structure of the nanocrystal responded to these different treatments to understand the molecular-level driver of crystallinity in these nanoparticles. One of my favorite parts of this project is the crystallinity metric we defined to quantify the degree of crystallinity in the simulation. This was a challenging task, and no one has really established a good way to do this. We decided to base the metric from the RMSD- which basically describes the amount of deviation of the atoms in the nanoparticle from their original lattice positions. We time-average the RMSD (since it can vary quite rapidly during the simulation), and normalize the value for any given simulation against the minimum deviation (RMSD for a simulation with no excipients), and the maximum deviation (the spacing between molecules in the lattice). This is summarized in the equation below.

\(\Gamma_{\text{effective}}= \frac{\frac{a}{2} - \langle \text{RMSD} \rangle}{\frac{a}{2} - \langle \text{RMSD}_{0} \rangle}\)

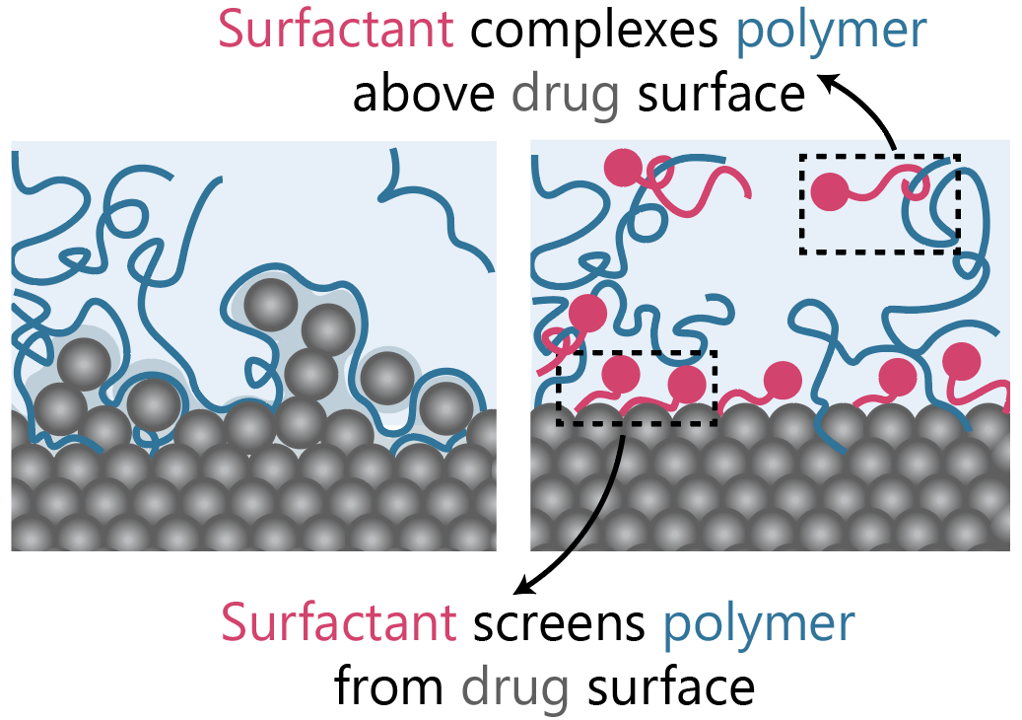

We discovered that two phenomena drive the crystallinity result of the surface. First, we find that the surfactant and polymer excipients we use experimentally compete at the interface, since both are surface active. However, since the surfactant is more surface active, it can outcompete the polymer, even at low concentrations, and ‘protect’ the surface from de-stabilizing polymer interactions. Additionally, the surfactant and polymer can themselves complex (a well-studied phenomena in soft materials), which de-localizes the polymer from the drug surface, and prevents it from disrupting the crystal structure and amorphizing the surface.